| <노래는 부르지 않을 것입니다 I am not going to sing, performance and installation>, 2015 |

||

|---|---|---|

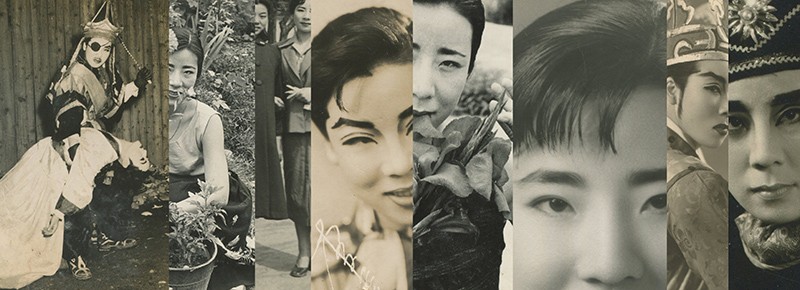

| 1950년대, 여성국극(Yeosung Gukgeuk)의 황금기에 빼어난 “가다끼(남역 조연으로 ‘악역’을 뜻하는 여성국극 현장의 은어)”로 이름을 날리던 배우 이소자는 ‘소리(판소리)’를 하지 못한다는 이유로 늘 조연의 자리에 머물러야만 했다. 물론 ‘가다끼’로서의 특화된 유명세는 언제나 그에게 큰 자부심과 삶의 동력을 제공했지만, ‘니마이(남역 주연으로 여성국극 공연과 관극의 핵심이 되는 역할이다.)’역을 향한 열망은, 이미85세가 된 늙은 배우에게 일생의 여한이다. 여성국극은 판소리를 그 음악적 기반으로 삼아, 한국 전통연희의 다양한 특징들을 혼합해 무대화하는 창무극의 한 종류이다. 서구의 오페라나 뮤지컬과 흡사한 양식을 띄지만 모든 배역을 오직 여성들만이 연기 해야만 하는 특수한 양식을 가진다. 따라서 여성국극 배우들 중에서도 주요 남역을 맡는 배우들은 소리와 춤에 능해야 할 뿐 아니라 남성을 연기하는 성별수행을 혹독하게 훈련하게 된다. 당시 ‘소리’에 능했던 여성들은 대개 ‘기생’출신의 여성들로 소리, 악기, 춤 등을 권번이라 불리우던 기생학교에서 수련한 경우가 대부분이었다. 따라서 당시, 여성이 예술적 기능을 보유하고 있다는 것은 기실 기생출신이라는 말과 다름아니었고, 또한 기생이란 호명은 단지 예능보유자를 이르는 것 이상으로 성적으로 방종한 여성을 천시하는 사회적 혐오의 시선이 포함되어 있었다. 이소자는 이러한 세상의 편견에 노출되는 것을 두려워 한 탓에 끝내 소리를 배우지 않았고, 그로 인해 영원히 남역 주연이 될 수 없었다. 그러나 주연이 될 수 없었기 때문에 누구보다도 악랄한 남자인 가다끼를 연기할 수 있었다. ‘나쁜 남자’라는 남성의 이미지는 매우 전형적인 ‘남성-되기’의 기술을 또한 제공한다. 이 작품은 여성국극 남역배우 이소자의 삶 뒤에 포진한 이와같은 성별의 문제들과 성차의 아이러니를 무대화 함으로써 사회적으로 반복되고 강요되는 성별표현의 허상을 공격하고 해체한다. |

Though renowned as an outstanding kataki (meaning “villain,” this is a theater slang designating a supporting male role) in the 1950s, the golden age of Yeosung Gukgeuk (traditional Korean female theater), performer So-ja Lee was always relegated to supporting roles because she could not sing a song, the musical basis of the genre. Of course, her fame as a master kataki was a constant source of considerable pride and energy in life. Nevertheless, the unfulfilled passion for the nimai (a word referring to the leading male role, this was the flower of Yeosung Gukgeuk for performers and audiences alike) is an enduring regret for the now 85-year-old performer.

Yeosung Gukgeuk is a type of musical and dance theater that, based musically on the pansori(Korean traditional story-singing), combines and stages the diverse characteristics of traditional Korean performing arts. Although similar in mode to the opera and the musical in the West, it is distinguished by the fact that all roles must be played by women only. As a result, from among Yeosung Gukgeuk performers, those who mainly play men’s parts must not only be adept at singing and dancing but also receive rigorous training in gender performance to play male roles. In this era, women skilled in the pansori were mostly former gisaeng (professional female entertainers akin to the Japanese geisha), having learned to sing, play musical instruments, and dance at private gisaeng schools called gwonbeon. Consequently, at the time, for a woman to have artistic skills meant that she in fact was a former gisaeng, and the label of gisaeng went beyond simple expertise in the arts and implied dissolute women and society’s ensuing contempt and hatred for them. Due to her fear of being exposed to such prejudices of the society, So-ja Lee did not learn to sing the pansori to the end and therefore could never play the leading male role. However, precisely because she could not play the leading male role, she was able to play the part of the kataki, a man more evil than any other. The male image of a “bad guy” also provides a very typical technique of “becoming man.” By staging such problems of gender and the irony of gender differences hidden behind the life of Lee, a male-role actress in Yeosung Gukgeuk, this work attacks and deconstructs the illusion of gender expression that is socially repeated and forced. |

|